A Comparison of XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost

Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs) are a family of powerful Machine Learning models. This article investigates three of the most popular GBM libraries: XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost. We begin with an overview of how GBMs work before diving into the advantages, disadvantages and special features of each model. Finally, we conduct two experiments followed by their results and conclusions.

1. Gradient Boosting Machines

GBMs are a popular technique both in industry and in current machine learning research. To understand how they work, let’s divide gradient boosting machines into two parts by their name: “boosting” followed by “gradient”.

The central idea behind boosting is that many simple models can be combined together to form a single powerful predictor. These simple models are known as “weak learners”. Boosting adds weak learners together sequentially to the existing model, beginning with a single weak learner. Each new addition is selected to improve the performance of the overall model in a greedy fashion and they don’t alter the predictions of previous weak learners. Typically, weak learners can be as simple as decision trees.

GBMs use boosting to combine these weak learners and seek to minimise the residuals in the data (the difference between the predictions of the model and the true response values). After a new weak learner is added to the model, the difference between the true response \(y\) and new prediction \(\hat{y}\) becomes the new target of the next weak learner, i.e. new weak learners are added to predict the new residuals iteratively. This is where the “gradient” aspect of GBMs comes in: minimising the loss function in a GBM is congruent to minimising some function using gradient descent. We add weak learners in a GBM to reduce the loss step-by-step, by moving in the direction of the residuals.

GBMs often provide very strong predictive accuracy - they are one of the most popular models in data science competitions such as Kaggle. They are flexible and versatile, e.g. by being able to optimise a variety of loss functions and in handling missing data. However, GBMs are highly prone to overfitting and they can be computationally expensive.

Further reading

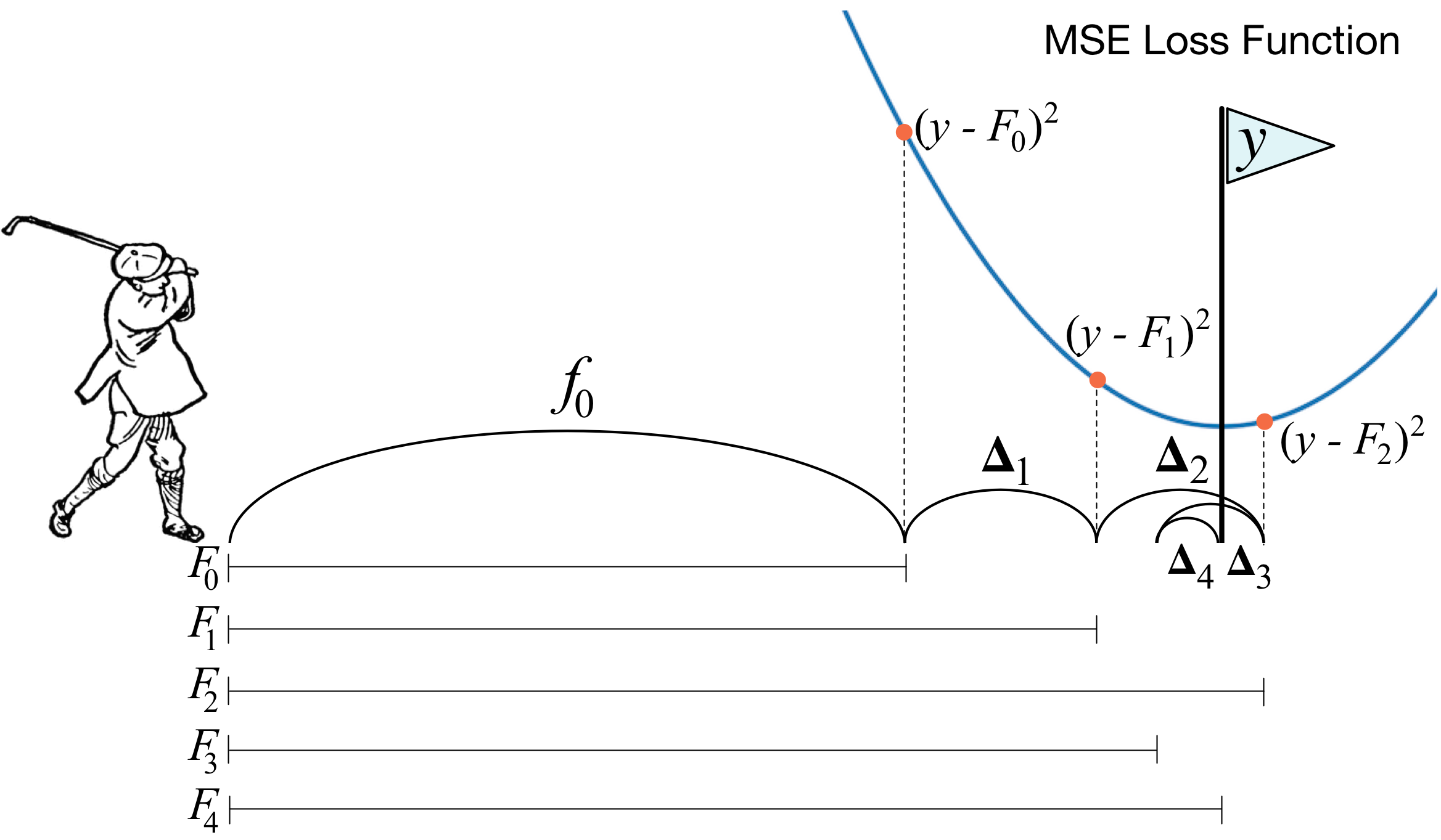

There are an abundance of resources available on the topic of GBMs. T. Parr and J. Howard provide a fantastic and intuitive explanation of gradient boosting [1]. They describe a clever analogy of gradient boosting to hitting a golf ball, with an image shown below. Naturally, J.H. Friedman’s original paper [2] on GBMs is a must read to gain a full understanding of these models.

A golfing analogy of gradient boosting from explained.ai [1], where F represents the prediction of overall models, Delta is the iterative increment of the weak learners and y is the response variable.

2. XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost

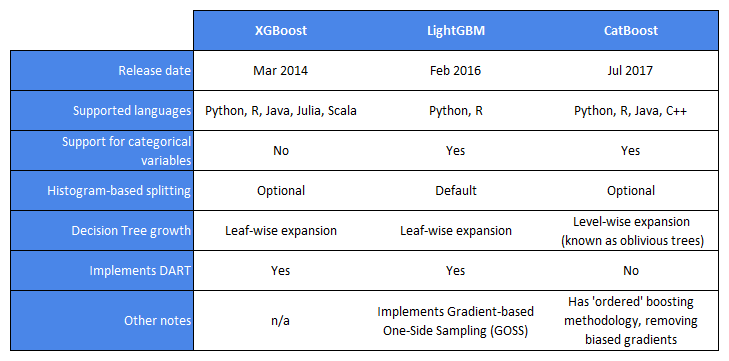

XGBoost [3], LightGBM [4] and CatBoost [5] are three of the most popular GBM libraries in recent years. Whilst they are all based on the same theoretical model, they differ in their implementation of some of the main features of gradient boosting:

- Categorical variable support: Datasets may contain categorical features. Some models require these to be pre-processed (e.g. using one-hot encoding) and others can deal with this inherently.

- Decision Tree splitting: Decision Trees are commonly used as the weak learners in GBMs. They operate by splitting the data iteratively into smaller subsets, trying to find the best split per feature (as in Random Forests). One method of splitting is ‘exact’ splitting searching through all possible splits which can be very expensive for continuous variables. Another method is to use histogram-based splitting, an ‘approximate’ splitting technique. This approach discretises the continuous variables’ values into bins, reducing the number of splits and making the search over splits faster.

- Decision Tree growth: Level-wise expansion grows a decision tree by splitting leaves from left-to-right and top-to-bottom in a depth-first approach. On the other hand, leaf-wise expansion iteratively splits the leaf in the decision tree that leads to the greatest improvement in the loss function. This is a greedier method as it grows the tree by finding the best split each time, though the trees aren’t usually as symmetrical as level-wise expansion.

- Dropout Additive Regression Trees (DART): DART is similar to dropout in neural nets and has the same purpose of trying to prevent overfitting. A random subset of trees are ‘switched off’ when fitting the residuals for learning the next decision tree to be added to the model.

- Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) : The explanation of gradient boosting in Section 1 outlines the similarity between gradient descent and training a GBM. GOSS is a technique that focuses on data points with larger gradients that will have more impact during training. It chases these larger gradients by giving them higher weights before learning the next decision tree.

The table below gives an overview of the three models and some key differences:

3. Experiments

There are many experiments that benchmark the speeds and performances of GBMs against each other with widely varying results [6]. Here we conduct experiments on two different datasets. Since a fair comparison of models through such experiments is a difficult problem [7], any results of model benchmarks should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Datasets

The performances of XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost are compared on two different datasets:

- Olympic Athletes: Contains a record of athletes in the Olympics, including a selection of their biological and team information, the Olympic year, sport, and what type of medal they won (if appropriate). The aim is to predict whether an athlete has won a medal. The response is a binary variable and there is a heavy class imbalance present.

- US Flight Delays: Contains a record of flights in 2015 between US cities, including the flight dates and times, journey details and any delays. The aim is to predict the delay upon arrival. This dataset has a nice balance of categorical and non-categorical features.

Standardised benchmarking datasets (e.g. Higgs or Epsilon) are frequently used in literature as they have appealing properties - this experiment uses two different ones for practical purposes and my own interest.

Methodology

Each dataset is cleaned before modelling occurs, such as removing features that aren’t useful for prediction and removing null values in the response variable.

For XGBoost, categorical features must be encoded into a different form as it cannot handle categorical features directly. One-hot encoding is used if there is a small number of categories in the feature whilst if there are many distinct categories then binary encoding is used. This saves on computational memory and time without sacrificing performance [8]. Also, exact decision tree splitting is used in XGBoost and CatBoost as they give theoretically greater accuracy than approximate splitting (and are their default methods).

After cleaning the dataset, the following steps are used (as recommended in [9]) to train and fit GBMs:

- Set no. of weak learners

- Tune other hyperparameters

- Train final no. of trees and learning rate

- Fit final model with these optimised hyperparameters

Scikit-learn’s cross validation and grid search functions across all models. Grid search is used instead of random search/Bayesian optimization across the hyperparameter space, though the others are more than valid approaches as well.

The implementations of both experiments can be found in my experiments github repo.

4. Results

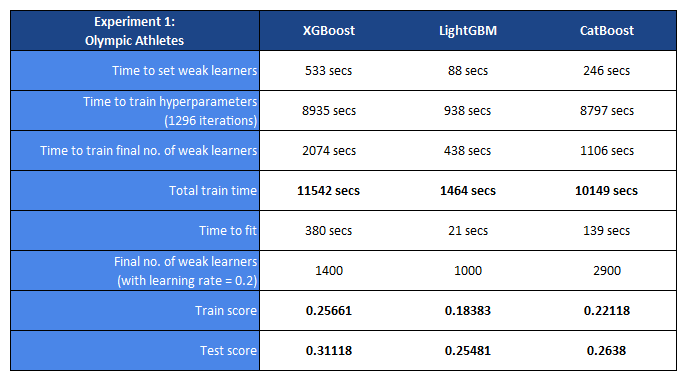

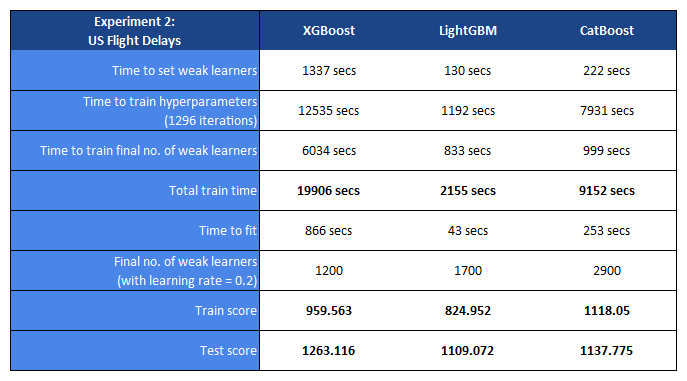

In the first experiment, the accuracy of the models are reported as the log loss. In the second experiment, the MSE error is used.

Each GBM model was trained using 32 vCPUs on Google Cloud Platform. Evaluation is conducted on a hold old test set, with a size ratio of 80:20 between training and test sets for each dataset.

5. Conclusion

These experiments compare the speed and accuracy of XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost on two different datasets. In both experiments, LightGBM performs the fastest whilst XGBoost is significantly slower. With the first experiment, CatBoost’s training time is slower than that of XGBoost’s. It would be expected that both XGBoost and CatBoost would have a lower training time if using approximate decision tree splitting, however this may impact the accuracy (as mentioned in the Methodology section).

The accuracy of predictions made by LightGBM is also the best on both datasets, with CatBoost close behind and XGBoost some way off. However, it appears that LightGBM is most prone to overfitting as well if we compare the training and test scores.

As noted before, one should be careful with stating any such conclusions with confidence - as one paper has summed up when comparing GBM performances: “Each library works better in different setups and on different datasets” [7]. It would not be surprising if a slightly different methodology, e.g. using Bayesian Optimization instead of grid search or using different datasets, gave varying results. The type of problem, the nature of the data and the availability of resources should always be considered when selecting the best GBM (and indeed machine learning model) to use.

References

[1]: T. Parr, J. Howard. How to explain gradient boosting. https://explained.ai/gradient-boosting/index.html. 2018. Accessed Dec 2018.

[2]: J.H. Friedman. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Annals of Statistics, 29:1189–1232, 2000.

[3]: T. Chen and C. Guestrin. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22Nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 785–794. ACM, 2016.

[4]: G. Ke, Q. Meng, T. Finley, T. Wang, W. Chen, W. Ma, Q. Ye, and T.-Y. Liu. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, pages 3146–3154. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017.

[5]: A. V. Dorogush, A. Gulin, G. Gusev, N. Kazeev, L. Ostroumova Prokhorenkova, and A. Vorobev. Fighting biases with dynamic boosting. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.09516, 2017.

[6]: A. Anghel, N. Papandreou, T.P. Parnell , A. De Palma and H. Pozidis, Benchmarking and Optimization of Gradient Boosted Decision Tree Algorithms. Workshop on Systems for ML and Open Source Software at NeurIPS. arXiv:1809.04559. 2018.

[7]: A.V. Dorogush, V. Ershov, D. Kruchinin. Why every GBDT speed benchmark is wrong. arXiv:1810.10380. 2018

[8]: K. Potdar, T.S. Pardawala, C.D. Pai. A Comparative Study of Categorical Variable Encoding Techniques for Neural Network Classifiers. International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 175 – No.4, October 2017

[9]: A. Jain. Complete Guide to Parameter Tuning in Gradient Boosting (GBM) in Python. https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2016/02/complete-guide-parameter-tuning-gradient-boosting-gbm-python/. 2016. Accessed Dec 2018.